bpfilter 2023 H1 status report

There have been a lot of changes on bpfilter in the past half, I’ll try to summarise all of it within this report! For a 30min summary, you can check bpfilter’s presentation at LSFMM+BPF this year!

Let’s summarise

6 months ago, bpfilter was a kernel usermode helper. Meaning a kernel module that would start a userspace program once loaded. It would then hook to getsockopt() and setsockopt() to catch iptables’ calls and bypass the iptables’ backend.

While this design had a lot of advantages over a standard kernel module, it wasn’t exempt from disadvantages compared to a full userspace program:

- Getting reviews and feedback from kernel maitainers can be long, leading to slower iterations.

- Lack of flexibility in development and limited use cases as

bpfilterwas highly tied toiptablesand its usage. - Some features could not be developed because of the usermode helper constraints.

Eventually, the decision was taken to change bpfilter into a userspace program (fully userspace, not a usermode helper anymore). bpfilter could then be removed from the kernel tree, to live in a dedicated GitHub repository. As you can see in the first commits in the official GitHub repository, bpfilter was for a time available as an out-of-tree kernel module, before becoming a userspace program.

What about the usermode helper in the kernel tree? It still lives there, as it’s not harming anyone. Eventually, I’ll send a patch to remove this code, as it’s not needed anymore.

Long story short: 6 months ago, bpfilter was a backend for iptables. Now, iptables is a front-end for bpfilter.

Moving bpfilter to userspace

I was intentionally vague in describing bpfilter as a “userspace program” to leave all the details in this section, so let’s see exactly what this means!

Moving bpfilter to userspace is a big piece of work; let’s define what this involves, just to be clear:

- All the kernel-specific code has to be removed. This can be very tedious, depending on the amount of internal APIs used. For example, many BPF instructions (e.g.

BPF_ALU64_IMM) are only defined in the kernel’s internal API. Another noticeable miss is the kernel’s linked list, which I had to rewrite (and drop unnecessary constraints on the way). - Move away from the

iptables-specific design and implementation:bpfilteronly supportsiptables, so it is internally very close toiptables’ internal structure and APIs. Havingbpfilteras a userspace program would allow more clients than justiptablesbut requires decouplingiptables-specific code. - Ensure

iptablesstill work. Thebpfilterkernel module could hook to theiptables’getsockopt()andsetsockopt()calls, and bypass the kernel to answer the calls directly. This is impossible from userspace, so I had to find a way to preserve this feature.

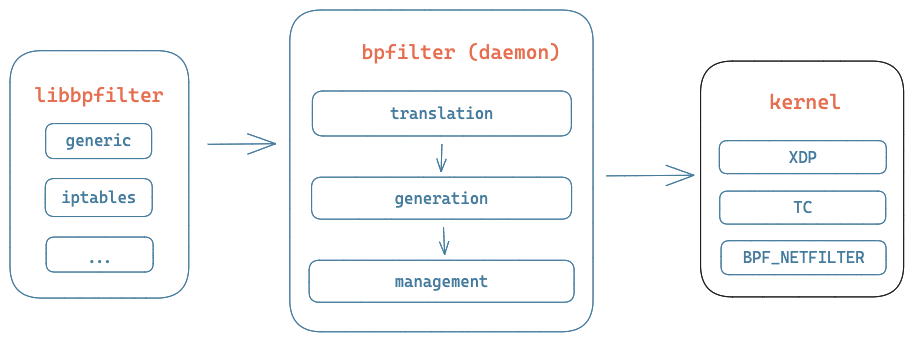

The choice settled on having bpfilter split into two parts:

- The daemon listens on a Unix Domain Socket (UDS). It processes incoming requests according to the content and sends the response back. It can generate a BPF program from scratch and attach it to the kernel.

- The library communicates with the daemon through the UDS. It’s lightweight and aims to be linked to the client. The library performs no complex operation: the daemon handles the heavy work.

Design

Let’s have a look at the main structures used in bpfilter:

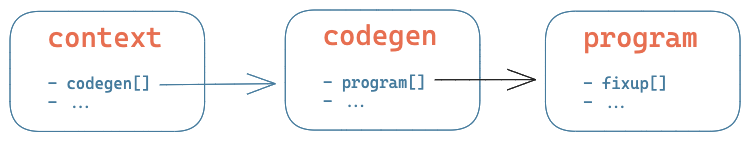

- Context (

bf_context) is the global context of the daemon, used to store the current state of the application. The context can be serialised to disk and restored, which is necessary if we want to restart thebpfilterdaemon without losing the state of loaded BPF programs and maps. Serialised data is also used to store client-specific data: for example, withiptables, it stores the set of rules iniptablesformat, so we don’t have to translate the BPF programs back intoiptablesinternal structures for each request. - Codegen (

bf_codegen) is the structure used to represent filtering rules for a(front, hook)tuple. For example, all theiptablesrules attached to theiptables’INPUThook will be stored within the same codegen. This way, rules are grouped together and generated into the same BPF program for a common(front, hook), while fronts remain independent from each other. - Programs (

bf_program) are… the BPF programs. Currently, there is 1 BPF program generated for each interface, for each(front, hook)set, allowing for interface-specific filtering rules. Each program has its own BPF map to store the rules’ counters: the number of packets and bytes processed by each rule.

To summarise, the global context will store a codegen for each (front, hook) tuple, generating a BPF program for each interface.

More about the daemon

The daemon will listen for incoming requests on a UDS. Each request will contain details about the source (e.g. iptables), the actual request (e.g. replace filtering rules, or fetch counters), and the client-specific data that form the request (e.g. list of rules or counters to fetch).

When the request is received, it’s time for translation: the daemon will translate the client-specific data into a generic format specific to bpfilter; bytecode generation can be shared between multiple fronts. Because of this structure, adding support for a new front (say Tupperware Firewall) comes down to adding the code to translate this front’s data format. The generic data is sent to the generation function after the translation.

Before we continue, let’s talk about “flavor” (or “flavour”), as it’s a term used in the codebase. Do you see how the prototype of a BPF program’s main function differs between TC and XDP? And so is the return value’s meaning? And so are multiple other things, which depend on the BPF program type? Well, from

bpfilter’s point of view, that’s a “flavor”. It’s used to generate boilerplate BPF bytecode specific to the BPF program type, so all the programs (whatever their “flavor” is) could be generated the same way.

The BPF program generation feeds from the generic bpfilter data structures: codegens from the request are provided by the translation function, and the generation function will then create the BPF programs for it. Using the flavor-specific callbacks (struct bf_flavor_ops), it will generate a boilerplate to store the packet size, initialise a couple of registers, and then unroll all the filtering rules into BPF bytecode to be evaluated sequentially at runtime. When all the rules and the code for counters update are generated, the programs are pushed to the management function of bpfilter.

The last part of the process is management (for lack of a better name). This part will use the flavor-specific functions to load the BPF programs to the kernel and attach them to their hook. Any existing bpfilter program previously loaded and attached for this (front, hook, interface) set will be unloaded.

And what about the library?

Well, as I described earlier, it’s lightweight, so let’s keep it short. libbpfilter currently offers an iptables-specific interface. Eventually, a generic front-end will be available. The idea behind libbpfilter is to simplify its usage as much as possible by providing API using client-specific data.

What does it look like for iptables? You’re probably wondering. Let’s have a look:

#if defined(ENABLE_BPFILTER) && !defined(_LIBIP6TC_H)

if (handle->use_bpf)

ret = bf_ipt_replace(repl);

else

#endif

ret = setsockopt(handle->sockfd, TC_IPPROTO, SO_SET_REPLACE, repl,

sizeof(*repl) + repl->size);

if (ret < 0)

goto out_free_newcounters;

What you can see above is part of an iptables proof of concept to demonstrate how would bpfilter be integrated (more on that later). Let’s skip the #if and #endif shenanigans: we see a three-line change to support bpfilter in iptables. Either handle->use_bpf is true, in which case we call bf_ipt_replace() from libbpfilter, or it’s false, and we use the old setsockopt() behaviour. As you can see, bf_ipt_replace() uses ipables’s data structures (repl) without modification, leading to a simple integration.

Fresh new features

That was a lot of things, but wait, there’s more! The previous section described the work I had to do to have bpfilter running as a userspace program so that we could expect the same features as bpfilter.ko. But I’ve added more features on the way; some are implied in the previous sections, but some are not discussed. Here is a list of some of the features added in the past months:

- Support for functions: previously, all the code in the generated BPF program was inlined. It worked great, but some features (such as updating the counters map) were generated multiple times in every BPF program (1 for each rule). Now, during program generation, a fixup for a function call can be added to be processed later. Then,

bpfilterwill check the function call fixups declared for a givenbf_program, add the relevant functions after the program’sexitinstruction, and update the jump offset of the fixup! - Support for multiple interfaces was discussed in the previous section. While the codegen structure is inherited from

bpfilter.ko, the was no support for more than one static interface. Hence,bf_programhas been introduced. Abf_codegenwill contain a program for each interface (except for the loopback interface) and generate eachbf_programaccording to the rules to attach to each interface. As a result, we can now doiptables -I INPUT -i enp0s5 -j DROP -p icmp! - (Un)serialise

bpfilter’s context was also discussed in the previous section. It comes from a comment from my LSFMM/BPF talk in May: what happens if we restartbpfilter? At the time,bpfilterwould forget all the loaded programs and maps! It’s not the case anymore:bpfilterwill serialise its internal state to/run/bpfilter.blobafter each write operation (i.e. operation modifying the filtering rules), then restore its internal context from it on start (or restart). - Overall code quality checks: I like my code style to be consistent, but it’s 2023 I shouldn’t spend time enforcing it, so

clang-formatwill do it for me, thanks to.clang-formatinbpfilter’s source code root folder. A.clang-tidyfile is also present, even though checks are subject to change. A coverage target is available (make coverage) to write a nice HTML coverage summary (see$BUILD/doc/coverage/index.html). Finally,make docwill generate the documentation with Doxygen and Sphinx (see$BUILD/doc/html/index.html). Documentation would need some love, but it’s only the beginning, and I expect it to be more complete and precise over time. - A lot of minor improvements here and there!

Last but not least, and also not a new feature, I’ve been working on an iptables integration proof-of-concept! You can get it on GitHub. It’s straightforward to integrate to libbpfilter (see the last two commits), this fork will behave exactly as iptables would, but if you pass the --bpf flag, then it uses bpfilter under the hood!

What’s next?

2023 H2 will be focused on improving bpfilter support for iptables, creating a proof-of-concept for nftables, and supporting more and more features: IPv6, connection tracking…